Editor's note: This story was updated Sept. 25, 2025, to include John Turchi's new appointment as inaugural chair of the Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Pharmacology.

John J. Turchi’s first exposure to the world of medicine came during his youth.

His father, a practicing physician in Philadelphia, would occasionally bring his children along to the hospital to get a glimpse at his career. Walking alongside his father past medical stations, hospital rooms and patients, Turchi left those visits with one solid takeaway.

“This is not for me.”

It was then that he knew what he didn’t want to do, at the very least. Finding his real interest took a bit more time.

Turchi, PhD, attended Clemson University in South Carolina and began his academic career studying architecture, a field he was neither all that interested in nor admittedly proficient in. Instead of preparing for the architecture coursework, Turchi spent his time with teammates on Clemson’s lacrosse team. Eventually he got to talking with a senior on the team about his biochemistry senior thesis research project.

Chemistry had been something of a strong subject for Turchi in high school, coming to him more easily than others. Here, talking with a biochemistry major, the intrigue was immediate, and questions began to flow: What system are you using? What techniques are there? Why did this happen?

The conversation came to a head when the senior countered with a question of his own: “Have you ever thought about being a biochemistry major?”

Turchi was directed to an advisor in Clemson’s biochemistry program. That meeting went similarly, with the topic turning to that advisor’s research and Turchi asking as many questions as he could get in. The advisor reached the same conclusion as his teammate: Turchi should switch majors.

He hasn’t looked back from there. Turchi’s career has taken him from Clemson to the University of Missouri for doctoral studies in biochemistry and on to the University of Rochester for postdoctoral work in its Department of Biochemistry and cancer center.

Now Turchi is the Tom and Julie Wood Family Foundation Professor of Lung Cancer Research and will soon be the inaugural chair of the Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Pharmacology at the Indiana University School of Medicine. He is also the executive director of the Tom and Julie Wood Center for Lung Cancer Research at the IU Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center, leading research efforts toward a better understanding of lung cancer and ways to treat it.

He’s had an interest in understanding how cancer cells respond to DNA damaging therapeutics since his career began. One such therapeutic is Cisplatin, developed decades ago at the IU School of Medicine by Lawrence Einhorn, MD. Cisplatin is curative for certain cancers, most notably testicular cancer, but lung cancer is less responsive and often develops resistance to treatment.

Turchi arrived at IU with a novel approach to make platinum-based, DNA-damaging therapies like Cisplatin more effective for lung cancer. It was a risky move at the time, but the approach has paid off with multiple potential drugs under development.

Faculty members such as Shadia I. Jalal, MD, Catherine R. Sears, MD and Einhorn himself have offered incredibly valuable insights which have proven instrumental in Turchi’s work.

"We have incredible collaborations with our clinical colleagues and physician-scientists,” Turchi said. “Interactions we have with them are unique to IU. I’ve been a lot of other places, and the basic science-physician collaborations just don’t happen.”

Turchi’s team has found that the process cancer cells undergo to replicate their DNA during cell division is fundamentally different than the process for non-cancer cells. Understanding the differences in this process can create vulnerabilities for cancer cells that can be targeted through therapies in a way that doesn’t harm non-cancer cells, Turchi explain.

“If you just put things in that stop DNA replication, it kills the cancer cells, but it also kills normal cells resulting in horrible side effects,” Turchi said. “But if you understand the differences between how cancer and normal cells go through that replication process you can target those things specific to the cancer cell replication.”

The group’s current projects work with two proteins involved in the DNA replication process: Replication Protein A (RPA) and a protein called Ku.

The team’s recent work with RPA has involved developing small molecules that target the protein-DNA interaction. Some of these molecules have drug-like properties, and the team is in the process of getting them into the FDA approval process for clinical trials.

Turchi is particularly pleased with the team's recent work with Ku. For the first time, the group has shown they can affect it in a way that results in cancer cells developing an increased sensitivity to another DNA damaging therapeutic modality, ionized radiation. The project is moving on to identifying a clinical candidate, Turchi said.

“One of the most common therapeutic interventions for cancer treatment is radiation therapy,” Turchi said. “We’ve been able to demonstrate that targeting this specific protein is very effective in combination with radiation therapy.”

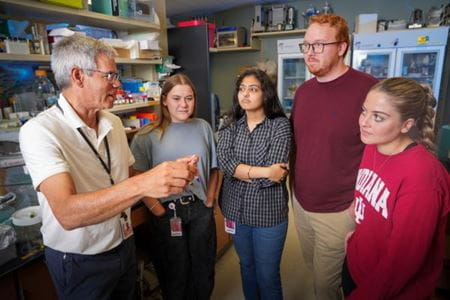

Turchi’s interactions with his lacrosse team and advisors at Clemson played a pivotal role in his path to becoming a researcher. Now he provides similar help to younger researchers and trainees in his lab, his favorite part of the job.

The design of his lab is very intentional. He has a small office with no windows that’s as close to the lab as he could get it to be without actually being in the lab. The best part of his day is when he can make the short walk from that office to the lab and, just as he did at Clemson decades ago, ask questions.

He wants to know what the graduate students and postdoctoral trainees are working on that day so he can talk science and learn their perspectives. He wants to see what any high-schoolers and undergraduates have learned in the lab setting and make sure all the trainees are getting the most out of being there.

Former members of Turchi’s team have gone on to run clinical practices with labs of their own, pursue independent positions as scientists, work in biotech, or continue their studies in graduate school. The vast majority stay in science, Turchi said.

He’s not wearing lacrosse gear anymore, but he still knows what’s best for a team.

“The long-lasting legacy of what we do are the people who come out of the lab who will be doing scientific research in the future that is going to answer the next big question,” Turchi said.