Scientists know inflammation plays a role in Parkinson’s disease. But instead of being something to fight, could inflammation be part of the cure?

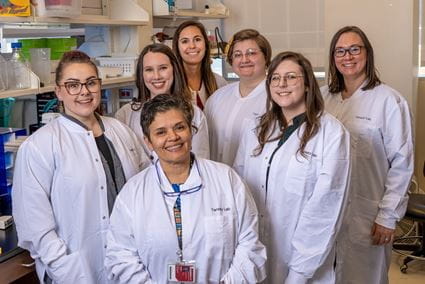

“I call it paradigm-shifting work,” said Malú Tansey, PhD, of the neuroimmunology research her lab is doing at the Indiana University School of Medicine. Recently relocated from the University of Florida, Tansey’s translational research brings cell-level science to IU’s already strong clinical research program in Parkinson’s disease.

According to the Parkinson’s Foundation, nearly 1 million people in the U.S. are living with this degenerative brain disease that causes movement issues which worsen over time. Nearly 90,000 people are diagnosed each year, with an estimated Parkinson’s-related health care cost of about $52 billion annually.

The IU School of Medicine is among just 40 medical centers in the U.S. designated as a Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence.

Tansey was recruited to expand neurobiology research at IU’s Stark Neurosciences Research Institute. Her lab likes to “think outside the brain” when it comes to potential causes of Parkinson’s and other neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s.

“For many years, the field has been very brain-centric,” Tansey said. “As we learn more, we see that Parkinson’s is a multisystem disease that has early manifestations outside the brain, like in the gut and the peripheral circulation and autonomic nervous system. And you start to think, well, maybe it didn’t start in the brain.”

‘A little closer to the cure’

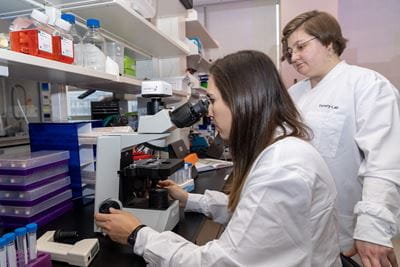

“Our role is to play detective,” Tansey said. Her team, including four early-career scientists who relocated with her from Florida, explores the role of the immune system response — tracking clues of changes that happen long before the disease reaches the brain.

“It’s not just a neuronal problem,” Tansey said. “This is a neighborhood problem, a village problem that needs to be addressed holistically.”

“It’s not just a neuronal problem,” Tansey said. “This is a neighborhood problem, a village problem that needs to be addressed holistically.”

Becky Wallings, DPhil, a postdoctoral fellow in Tansey’s lab, is taking a fresh look at inflammation and how immune cell exhaustion, or ICE, might play a role as a person ages.

“Right now, we’re only just touching the tip of the iceberg in discovering the specific role of immune cell exhaustion in this disease,” Wallings said, noting the pun.

Inflammation is a key part of the immune system’s natural response to infection, tissue damage and other harmful stimuli.

“Over the last 20 years, the field has been looking at inflammation as something that is heightened in Parkinson’s disease and needs to be suppressed or quashed,” Wallings explained. “But my data suggests that if the immune system of an individual with Parkinson’s disease is already exhausted, then suppressing it further is going to be deleterious. So, we need to think about new therapeutic approaches that reinvigorate the immune system.”

Genetics also plays a role. Parkinson’s Foundation research found that about 13% of people with the disease have a contributing genetic mutation, likely influenced by environmental factors. Wallings’ recently published research deals with genetic mutations in the LRRK2 gene. She explains her discovery in animal studies by using a candle analogy.

Genetics also plays a role. Parkinson’s Foundation research found that about 13% of people with the disease have a contributing genetic mutation, likely influenced by environmental factors. Wallings’ recently published research deals with genetic mutations in the LRRK2 gene. She explains her discovery in animal studies by using a candle analogy.

“The genetic mutation was making the candle burn very, very bright when the mice were young, but the candle burns out a lot quicker,” she said. “As these mice were aging, they were acquiring this immune cell exhaustion phenotype, which has completely changed the way I view inflammation in Parkinson’s.”

The goal is personalized medicine — developing targeted drug therapies based on a person’s genetics, said Elizabeth Zauber, MD, a movement disorder specialist, professor of clinical neurology at the IU School of Medicine and director of the Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence.

The School of Medicine is a partner site for the Parkinson’s Foundation PD GENEration study, an international initiative that offers genetic testing and genetic counseling at no cost for people with Parkinson’s disease. This is important for understanding an individual’s prognosis as well as identifying people who might benefit from clinical trials.

“I personally feel it’s a really exciting time for Parkinson’s research when it comes to how much closer we are to understanding how to manipulate the immune system and develop new therapeutics,” Wallings said.

Recently, IU School of Medicine neurologists helped test Vyalev, a first-of-its-kind wearable pump to deliver the Parkinson’s drug levodopa continuously under the skin. Clinical trials led to FDA approval in October. Compared to taking a pill with the same medication, Vyalev was found to be more effective for keeping symptoms at bay.

Recently, IU School of Medicine neurologists helped test Vyalev, a first-of-its-kind wearable pump to deliver the Parkinson’s drug levodopa continuously under the skin. Clinical trials led to FDA approval in October. Compared to taking a pill with the same medication, Vyalev was found to be more effective for keeping symptoms at bay.

Tom Kundenreich, MD, is among the first Parkinson’s patients in Indiana to try the new system.

“It really has been a wonder,” he said. “To wake up and not feel awful has been a godsend.”

The wearable pump keeps a steady dose of medications in his system, even through the night. Kundenreich wonders if he might have kept practicing longer as a neonatologist, working with at-risk newborns, if he’d had the pump sooner.

“I’m looking forward to having a golf season on this pump to see how it affects my game,” he said.

It’s patients like Kundenreich who keep IU researchers motivated to find a way to slow — and eventually stop — Parkinson’s disease.

“There are a number of exciting things coming down the pipeline,” Zauber said. “We’re certainly getting closer.”

‘It takes a village.’

To counter a complex disease, a collaborative approach is required.

Zauber is an expert in deep brain stimulation (DBS) — a surgical procedure where electrodes are implanted in certain areas of the brain to help regulate abnormal movements. New technology enables brain activity to be recorded. IU recently hired a neurophysicist with expertise in brain recordings, along with more neurosurgeons to perform the surgical procedure.

Zauber is an expert in deep brain stimulation (DBS) — a surgical procedure where electrodes are implanted in certain areas of the brain to help regulate abnormal movements. New technology enables brain activity to be recorded. IU recently hired a neurophysicist with expertise in brain recordings, along with more neurosurgeons to perform the surgical procedure.

“DBS has been around for almost 30 years, but this new technology is allowing us to be much more precise in how we deliver the electricity to maximize the benefit and minimize side effects,” Zauber said. “Before, we didn’t have any direct feedback from the brain to see where the abnormal brain signals are. Adaptive DBS is just being launched, so that’s what’s on the frontier right now.”

Holistic therapies for Parkinson’s include exercises like Rock Steady Boxing, an intense exercise regimen developed by an Indianapolis patient. Zauber serves on the organization’s board and is studying Rock Steady’s effectiveness.

Along with physical problems like tremors, Parkinson’s can also cause non-movement symptoms. IU participated in a palliative care study through the Parkinson’s Foundation to address quality-of-life issues like sleep, mood and cognitive decline.

The Parkinson’s team brought on a chaplain for spiritual distress and a pharmacist to create educational resources about Parkinson’s medications. A researcher at the IU Center for Bioethics joined the team to study advanced care planning for people with Parkinson’s.

“We received international recognition from the Parkinson’s Foundation for the work that we’re doing as a team to provide holistic care for our Parkinson’s patients,” Zauber said.

“We received international recognition from the Parkinson’s Foundation for the work that we’re doing as a team to provide holistic care for our Parkinson’s patients,” Zauber said.

Back in the Tansey lab, the motto is, “It takes a village.”

“We need collaborations to answer these complex questions,” Wallings said. Her research is just one piece of the Parkinson’s puzzle. “You need many people at the table who have diverse skillsets, trainings and backgrounds to answer these really multifaceted questions that could unlock a cure.”