The rich tradition of excellence in clinical care, education and research in the Department of Neurological Surgery at the Indiana University School of Medicine goes back to 1949 when Robert Heimburger, MD, was asked to form the neurosurgery service and residency program at the Indiana University Medical Center.

As the first director of the Division of Neurological Surgery in the Department of Surgery, Heimburger recruited neurosurgeons and residents to Indianapolis over the course of the next decade-and-a-half — including department legends Robert Campbell, MD; John Mealey, MD; and John Kalsbeck, MD — and launched the ACGME-approved residency program. The division continued to blossom and grow under the leadership of Campbell as director for nearly three decades, from the 1960s to the 1990s.

Over the course of the next 35 years, four directors and chairs have led the division through its establishment as a full department and the development of a neuroscience hub of clinical care and research. These leaders advanced the department into a new age of leading-edge neurosurgery technology. With 75 years of worldclass neurosurgery expertise, the department has continued to be at the forefront among national and international leaders in how they treat patients, investigate new therapeutics and train the next generation of neurosurgeons.

Saving the life of an American heartland rock icon

Nearly two years after Robert Heimburger, MD, established the neurosurgery service at Indiana University Medical Center, the neurosurgeon performed a highly risky and experimental surgery on a newborn from Seymour, Indiana, born with spina bifida — a likely fatal birth defect.

That child was John Mellencamp — the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame singer-songwriter best known for hits in the 1980s like “Hurts so Good,” “Pink Houses” and “Small Town.”

Spina bifida is a birth defect that occurs when the spine doesn’t fully develop. This can cause damage to the spinal cord, nerves and brain. Heimburger, who performed the surgery on Mellencamp for 18 hours at Riley Hospital for Children in 1951, said in a journal article published in Surgical Neurology International about his career in neurosurgery, that medical experts at the time advised physicians to leave the defects in their back alone for six months.

Spina bifida is a birth defect that occurs when the spine doesn’t fully develop. This can cause damage to the spinal cord, nerves and brain. Heimburger, who performed the surgery on Mellencamp for 18 hours at Riley Hospital for Children in 1951, said in a journal article published in Surgical Neurology International about his career in neurosurgery, that medical experts at the time advised physicians to leave the defects in their back alone for six months.

"Most of the babies succumbed to meningitis in spite of extensive care provided by mothers, families, and experts," Heimburger wrote. "The normal faces and intelligent eyes of the babies who were brought for my examination caused me to think that they deserved better than to wait six months for surgery."

Mellencamp was one of three babies with spina bifida in 1951 at Riley Hospital.

"They did three operations," Mellencamp told CBS News in 2014. "One died on the table. Another girl lived I think 'til she was 14, and then she died — and then me. So, they basically cut my head ... laid it open, cut that thing off and then put all the nerves into my spine."

Heimburger wrote that he read a paper in a medical journal about better patient outcomes if the newborns had their spinal canals closed surgically soon after birth, so he began performing early surgical closure of their spinal defects. Heimburger told Advance Local in a March 2015 interview that Mellencamp’s spina bifida birth defect would have likely been fatal.

“Family physicians hearing of my willingness to do so would occasionally phone in the middle of the night to say, ‘Get the OR ready; I’m bringing one to you!’ The babies arrived held gently in the arms of a nurse or relative, often in the family physician’s car,” Heimburger wrote. “The family physicians liked to scrub in with me and a surgical resident for these operations.”

Mellencamp told CBS News that he didn’t know about the operation until elementary school when a student behind him pointed out to him a large scar on the back of his neck.

"And I said, 'What scar?' My parents had never told me anything had ever happened to me,” Mellencamp recounted during his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction speech on March 10, 2008. “I'm lucky. And my grandma, my entire life, from a little kid until she died, would always come up to me and whisper. She called me Buddy. And she'd go, 'Buddy, you're the luckiest boy in the world.' And I am."

In September 2014, Mellencamp finally met the 97-year-old Heimburger at Riley Hospital for the first time since the operation in 1951. Mellencamp saw an image of his spinal column at just nine days old during the visit and spoke with Heimburger about the surgery and faith.

"I'm 62 years old now," Mellencamp told CBS News in the 2014 interview. "I just for the first time saw the growth in the back of my neck. And it was just like 'Why didn't you guys show this to me earlier? 'Cause I woulda seen how lucky I am to even be here.'... I mean it was really an epiphany moment for me. And you just couldn't thank the guy enough."

Advancing techniques for more than 50 years

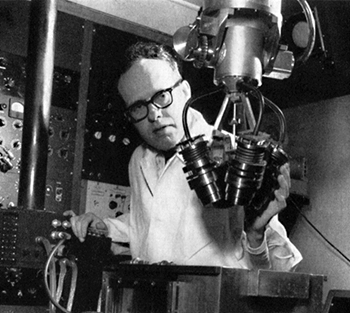

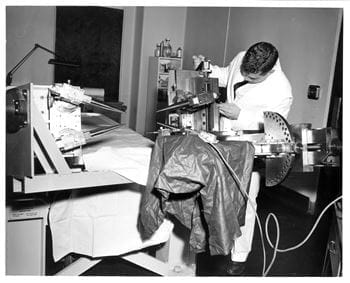

At a neurosurgical meeting in the 1950s, Robert Heimburger, MD, heard a presentation from research scientists William and Frank Fry on the development of the first focused ultrasound device that pinpointed brain lesions and destroyed selected tissue without damaging surrounding tissue in animals. Heimburger wrote about this meeting in Surgical Neurology International.

Heimburger later connected with the Fry brothers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, about his interest in collaboration. The Frys had already started working with Russell Meyers, MD, a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Iowa, in Iowa City to create a high-intensity focused ultrasound apparatus to “make very discrete brain lesions in patients.” The Frys had done extensive animal testing of their technology to that point.

In 1957, Meyers successfully conducted the first ultrasonic surgery on a human brain, which was covered in Time magazine later that year, according to a 2015 article in Physics Today written by William O’Brien and Floyd Dunn. For the focused ultrasound to reach the target in the brain, a section of a patient’s skull had to be removed to pinpoint the lesion. Heimburger visited the university to see these procedures and the research of the Frys.

“My 120-mile drives to Champaign-Urbana to visit the Fry brothers′ ultrasound laboratory became almost monthly,” Heimburger wrote. “With the help of relatives, I brought several patients with malignant brain tumors to the University of Illinois to receive HIFU (high-intensity focused ultrasound) in an attempt to diminish the spread of their malignant brain tumors. We found that chemotherapy and radiation treatments seemed to be enhanced by the HIFU treatments so that the patients had considerably longer than expected survivals.”

In addition to treating patients with Parkinson’s disease, cerebral palsy and cerebrovascular disorders, Heimburger and the Fry brothers were interested in the focused ultrasound device’s potential to treat brain tumors. In 1968, Heimburger took a patient who was referred to him who had a brain tumor in the center of her brain where physicians said couldn’t be reached by surgery. The young woman and her parents traveled to Champaign-Urbana to learn about the Fry’s laboratory and see if they would be interested in this experimental technique.

Heimburger used the ultrasound equipment to see the woman’s tumor more precisely, and he was able to remove the mass in the right temporal lobe of her brain, which he said, “contained all we could identify of her glioblastoma multiforme.”

Heimburger used the ultrasound equipment to see the woman’s tumor more precisely, and he was able to remove the mass in the right temporal lobe of her brain, which he said, “contained all we could identify of her glioblastoma multiforme.” “We took her back to Champaign-Urbana several times for HIFU therapy while her parents became increasingly impressed by the Fry brothers and their innovation,” Heimburger wrote. “We found that HIFU significantly improved the treatment results of the few malignant brain tumors we treated with ultrasound in addition to chemotherapy and radiation.”

The patient’s parents, Robert and Elizabeth Fortune gifted the university more than $250 thousand to move the Fry’s laboratory from the University of Illinois to Indianapolis, naming it the Fortune-Fry Research Laboratory.

"Moving the Fry Laboratory to IUMC (Indiana University Medical Center) enabled years of fruitful service and research on ultrasound uses in the brain, including imaging research, which was eclipsed by the invention of the computed tomography (CT) scan in the 1970s," Heimburger wrote.

During much of the 1970s, Heimburger led the use of focused ultrasound equipment developed by the Fortune-Fry lab on neurosurgical pediatric patients at Riley Hospital for Children with acute head injuries. The team used the equipment for diagnostic imaging of patients, while the researchers in the lab continued studying the effect of sonication of intracranial areas in animals.

Looking to the present, the Department of Neurological Surgery are still pioneers in stereotactic and functional neurosurgery. Faculty neurosurgeons have led the development of deep brain stimulation, a minimally invasive surgical treatment that involves placing fine stimulating electrodes into specific areas of the brain that control movement, and a more modern approach to focused ultrasound, spearheading both initiatives in the early 2020s.

Focused ultrasound thalamotomy is a cutting-edge, noninvasive operation, that’s a treatment for patients experiencing movement disorders who have not responded to medications. Advancing on the early surgeries of Heimburger and Meyers in the 1950s and 1960s, the current procedure has no incisions, drilling or burr holes. It instead directs ultrasonic waves to a small part of the brain that is responsible for the patient’s movement disorders condition.

Patients will usually see immediate improvement after multiple rounds of the ultrasonic waves. Throughout the procedure the amount of energy from the ultrasonic waves increases the heat needed to form a lesion to eliminate brain tissue that’s causing the tremor.

The cancer also spread to other parts of Armstrong’s body, including his brain. Twenty-five years old in 1996 and at the start of his career in competitive cycling, Armstrong met with Scott Shapiro, MD, a neurosurgeon specializing in neuro-oncology and spinal disorders.

Shapiro, who earned his medical degree and completed his neurosurgery residency program at the IU School of Medicine, often worked with Einhorn and Craig Nichols, MD, on consultations. He was their “go-to guy” for patients who had brain metastases or spine cancer from testicular cancer.

“Einhorn invented the treatment that cured testicular cancer, but there are a lot of other great oncologists in the oncology section at the school of medicine, so we would get lots of tumor patients,” Shapiro said. “People wouldn’t keep sending them to us if they we didn’t do a good job for them, and we did a good job.”

Shapiro performed the surgery that removed two metastases from Armstrong’s brain. IU was one of just a handful of places in the 1990s that had image guidance and brain mapping that made it possible to conduct simultaneous bilateral craniotomies, Shapiro said. The treatment, designed by Nichols, destroyed cancer cells in Armstrong without hurting his lungs allowing him to return to being a professional and successful athlete.

At the time, Armstrong had only won a few professional races – he later won seven consecutive Tour de France titles between 1999 and 2005.

Shapiro said, he removed brain metastases nearly every week in patients. It was integral to his surgical work and for many other neurosurgeons at IU.

“We were implementing relatively new technology,” Shapiro said, “but the basic concept of the surgery I had done a lot of, so for me it was just another day in the operating room.”

Neurosurgery faculty performing brain metastases tumor removals were able to improve patient outcomes with the assistance of interoperative CAT scans and MRI scans to image a tumor and verify its removal while a patient was still in the operating room.

Top destination for neurosurgery education

At the IU School of Medicine, the largest medical school in the country, neurosurgery training is historically one of the top medical specialties that students pursue when entering residency.

Paul Nelson, MD, chair of the department from 1992 to 2011, said many medical students at the IU School of Medicine were drawn to the neurosurgery program because of its breadth of clinical and research opportunities. Many medical schools, Nelson said, organize their clerkships to include only a neurology rotation; but at IU, students can spend their time in a neurology rotation or neurosurgery rotation, and in some cases can split between both groups.

“Students who interacted with us I think saw that we tried to make it pleasant for them and tried to give them plenty of experience both in and out of the operating room,” Nelson said.

Shapiro earned his medical degree at the IU School of Medicine and later matched at the school for his neurosurgery residency. After training, Shapiro joined department faculty and later became the residency program director, serving in that role for more than 30 years.

“All the faculty that I trained under were not only outstanding neurosurgeons, but they were good people and a joy to work with,” Shapiro said, “and I followed in their footsteps.”

Shapiro said the department developed an environment that was inclusive and supportive for medical students and residents. Each month, third-year medical students would rotate in the department, and fourth-year students spent most of the year in the department. They participated in lectures and assisted surgeons and residents in the operating room and clinic.

“We’re trying to get the spark there,” Nelson said. “Mentoring is something that I enjoyed doing, and I think everybody else enjoyed doing it as well.”

Shapiro said the breadth of neurosurgery gave students, and eventually residents, an opportunity to learn something new each day, whether that was about complex brain tumors and cerebrovascular conditions, spinal disorders, functional neurosurgery, pediatric neurosurgery or neurotrauma.

“We're one of the better programs teaching you how to do neurosurgery,” Shapiro said. “We were good at letting residents operate, under appropriate supervision, and as they got better and better, turn them loose. That’s how you truly train people to become great themselves.”