INDIANAPOLIS — An Indiana University School of Medicine physician scientist is making strides in understanding the molecular origins of fatty liver disease, a leading cause of liver failure in the United States. By identifying the critical role the urea cycle plays in its development, his findings could pave the way for new medications to treat this currently incurable disease.

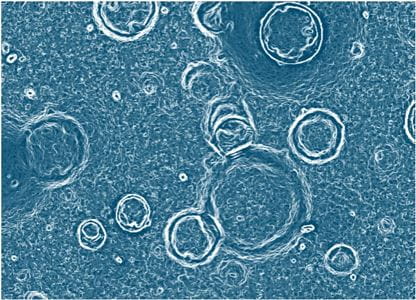

In a study recently published in Cell Metabolism, Brian DeBosch, MD, PhD, professor of pediatrics at the IU School of Medicine and the study’s corresponding author, uncovered a critical link between defects in the urea cycle, a key process in detoxifying ammonia in the body, and the development of fatty liver disease. Conducted during his time at Washington University in St. Louis, the study found that these urea cycle defects lead to secondary impairment in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, a key pathway for energy metabolism. This disruption results in inefficient calorie utilization and excessive fat storage in the liver, which can subsequently cause inflammation and fibrosis, contributing to the progression of the disease.

“Pediatric fatty liver disease can be much more aggressive and more difficult to treat than the adult forms of the disease,” DeBosch said. “Compounding this, there are no approved treatments for pediatric MASLD and MASH, even though MASH is fastest-rising in children. That is why our research is focused on addressing this incredibly urgent need.”

The two types of fatty liver disease are metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Both conditions involve excess fat buildup in the liver, which can result in liver failure if left untreated. The incidence of MASLD and MASH is rising rapidly among children, where the disease often presents more severely.

DeBosch collaborated on the study with Associate Professor of Surgery and Medicine Yin Cao, ScD, MPH at Washington University in St. Louis. Cao analyzed blood metabolites from a cohort of 106,600 healthy patients from the United Kingdom Biobank. Her examination revealed that certain metabolites associated with nitrogen and energy metabolism, as well as mitochondrial function, can predict the risk of severe liver diseases even in healthy individuals. Cao said the findings from this translational study, also backed by mouse research, underscore the critical role of the urea cycle in understanding severe liver diseases.

“MASLD and MASH are significant health concerns that are closely associated with other metabolic conditions and an increased risk of various cancers,” she said. “This discovery holds promise for breakthroughs in the prevention and treatment of these serious conditions.”

In a 2022 Cell Reports Medicine study, DeBosch and his team found that administering an enzyme called pegylated arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) significantly improved symptoms of fatty liver and obesity in mice, offering promising insights for future therapies. Their latest findings further suggest that targeting nitrogen handling in the liver, a process linked to the urea cycle, could be an effective treatment approach.

Additionally, their research demonstrated that giving mice a precursor to adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), an important intermediary that fosters TCA cycle function, also improved function in their study models. Looking ahead, DeBosch plans to continue exploring the effects of ADI-PEG 20 and NAD+ to investigate their molecular connections between the urea and TCA cycles.

"I want to explore the best pathways to target these defects so future drugs leveraging this biology can be more effective and precise in treating individuals with fatty liver disease," DeBosch said.

DeBosch joined the IU School of Medicine Department of Pediatrics in July 2024 to lead the newly established nutrition and molecular metabolism research program at the Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research. He is also the new co-division chief of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at Riley Children’s Health.

“We’re thrilled to have Dr. DeBosch join our team at the Wells Center and look forward to the innovative contributions he will bring to our new nutrition and molecular metabolism research program,” said Reuben Kapur, PhD, director of the Wells Center. “His expertise is invaluable as we work to enhance the health and well-being of children across Indiana.”

A nationally recognized expert in gastroenterology and nutrition, DeBosch aims to advance the understanding of the gut determinants of metabolic disease and develop innovative treatments that improve outcomes for pediatric patients. His laboratory focuses on researching diseases including fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes.

“I'm excited to join the IU School of Medicine and the Wells Center,” said DeBosch. "This opportunity allows me to collaborate with incredible physicians and scientists while continuing to prepare the next generation of experts in the field. I look forward to contributing to the center's mission of improving pediatric health outcomes in Indiana and well beyond.”

About the IU School of Medicine

The IU School of Medicine is the largest medical school in the U.S. and is annually ranked among the top medical schools in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. The school offers high-quality medical education, access to leading medical research and rich campus life in nine Indiana cities, including rural and urban locations consistently recognized for livability. According to the Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research, the IU School of Medicine ranks No. 13 in 2023 National Institutes of Health funding among all public medical schools in the country.

Writer: Jackie Maupin, jacmaup@iu.edu

Sources: Brian DeBosch, bdebosch@iu.edu, and Yin Cao, yin.cao@wustl.edu