Edmond Rogers, PhD, is not your typical first-year medical student. Rogers came to the Indiana University School of Medicine—West Lafayette campus with years of experience in traumatic brain injury research as co-developer of an innovative technology known as TBI-on-a-chip.

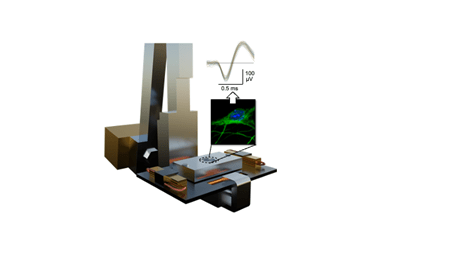

“The technology allows us to have this ‘brain’ on a microchip that we can visualize and record in real time,” Rogers explained. “With TBI-on-a-chip, we are deciphering the disease-causing mechanisms of trauma on the subcellular level, uncovering new biomarkers to improve diagnosis and novel targets for therapeutics.”

This technology gives researchers a unique way to study head traumas. They can watch biochemical changes happening from the moment of impact and then study how the resulting neural network breakdown contributes to diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

The story of how Rogers brought this pioneering technology from Texas to Indiana — transporting a large pendulum device with racks of custom Plexon neurophysiology recording systems in the back of a U-Haul — is something his Purdue University doctoral advisor, Riyi Shi, MD, PhD, said “should be made into a movie.” Today Shi and Rogers continue to refine the device developed by Guenter Gross, PhD, a retired University of North Texas professor who mentored them both — 30 years apart — as founding director of UNT’s Center for Network Neuroscience.

“Dr. Gross is an engineering genius,” said Shi, an endowed professor of applied neuroscience at Purdue and an adjunct professor of anatomy, cell biology and physiology at IU School of Medicine. “We are his scientific offspring.”

Shi has a history of collaboration with researchers in the Departments of Neurosurgery and Neurology and within the Stark Neuroscience Research Institute at IU School of Medicine aiming to develop an anti-acrolein therapy for traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis. TBI-on-a-chip has shown that acrolein levels can also be elevated after a blow to the head.

One of Rogers’ first published studies, co-authored with Gross before his retirement, proved this novel technology could record a concussion’s immediate effects on the electrical activity and connectivity of the brain, using cortical neuronal networks. Shi’s expertise in biochemistry and molecular cell biology analysis significantly empowered this technology and led to what TBI-on-a-chip is today — an innovative, non-animal model that can help scientists see what happens to the brain’s neural connections after impact.

From aspiring musician to serious scientist

Rogers’ part of the story begins as a music-loving kid from East Texas who ran afoul of his physiology professor. Because of frequent music gigs needed to pay for college, Rogers often missed classes. Gross admonished him, saying, “That’s no way to do science.”

A first-generation student, Rogers heeded the advice — he dropped Gross’ class and re-enrolled later when he had more time for science. Upon Rogers’ reappearance, Gross invited this quizzical student to visit his research laboratory. The experience would forever change Rogers’ path.

“I go to see this guy’s lab, and it’s incredible,” Rogers recalled. “They were growing brains on chips for multiphysics modeling and neurotoxicological studies. I fell in love instantaneously.”

Rogers never imagined he would one day drive Gross’ valuable, trauma-simulating machine 930 miles northeast to Shi’s lab at Purdue, where the two would advance their mentor’s research to new levels. Gross, the now-retired pioneer in microelectrode arrays (MEA), remains a frequent visitor to the lab.

“This is really a three-generation effort,” said Shi, who studied under Gross at North Texas in the late 1980s and now leads the Center for Paralysis Research at Purdue University, where Rogers is a visiting scholar. “Dr. Gross had 30 or 40 years of creating this technology that can give a concussion on a chip. His last student was Ed.”

Part of Rogers’ attraction to brain injury research comes from observing friends who served in the military return home with the aftereffects of repeated concussions or blast injuries. Long before joining Gross’ lab, Rogers struggled to understand the personality changes in a friend who experienced several “mild” brain injuries while deployed overseas.

“We all know people can behave differently after brain injury, but now we’re able to see it on a cellular level,” Rogers said. TBI-on-a-chip received major funding as part of a $1.3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Defense for brain injury research.

Although Rogers still loves making music — including guitar “jam sessions” with IU School of Medicine—West Lafayette Associate Dean and Director Matthew Tews, DO — he has discovered a passion that supersedes his musical interests. After earning his PhD in biomedical engineering from Purdue in 2023, Rogers now has his sights on becoming an academic physician specializing in neurology.

Although Rogers still loves making music — including guitar “jam sessions” with IU School of Medicine—West Lafayette Associate Dean and Director Matthew Tews, DO — he has discovered a passion that supersedes his musical interests. After earning his PhD in biomedical engineering from Purdue in 2023, Rogers now has his sights on becoming an academic physician specializing in neurology.

“IU and Purdue are known as rivals, but in the science community we’re not,” said Rogers, who has research collaborators and mentors at both institutions. “The West Lafayette campus offers an incredible atmosphere for research.”

How does TBI-on-a-chip work?

The big problem with studying biochemical changes resulting from a brain injury is obvious — they happen inside a human brain. Historically, TBI studies have been done on animals, which comes with ethical complexities. Other investigations look at human brains donated after death.

“Our novel TBI-on-a-chip system, which is currently only available here (Purdue), for the first time allows visual and electrical access to brain tissue during traumatic injury, with sub-cellular resolution,” Rogers said. “Furthermore, this approach reduces the total amount of experimental animals necessary.”

TBI-on-a-chip starts with cultured cells which are grown on transparent glass microchips and matured into “mini-brains.” It’s a miniature life support system which can maintain physiological parameters while withstanding high-impact, g-force blows from the pendulum, simulating different types of head traumas.

“Our lab is the pioneering lab,” Shi said. “No other lab can impact and study a culture like this.”

Engineering for the concussion device began decades ago when Shi was a grad student in Gross’ laboratory at North Texas. Shi went on to become the leader of Purdue’s Center for Paralysis Research, an interdisciplinary neuroengineering group that has a track record of moving basic science into clinical development. Shi also brings experience in commercialization as co-founder of startup company Andara Life Science Inc.

Scott Shapiro, MD, the Robert L. Campbell Professor of Neurological Surgery at IU School of Medicine, a longtime collaborator with Shi, was the chief clinical investigator for Andara’s patented paralysis treatments. More recently, Shapiro and Shi served as co-advisors on Rogers’ research fellowship through the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute.

TBI-on-a-chip is now an important part of the paralysis center’s strategy to develop brain injury treatments that could halt the development of dementia.

“Now that we have proven this model, we can take a step further and look at the resulting neurodegeneration to investigate non-hereditary Alzheimer’s pathogenesis, which is both the most commonly occurring form and a research area in which current models are limited,” Rogers said.

Growing collaboration in biomedical research

As much as he enjoys research, Rogers decided to become a medical doctor so he could one day also work directly with neurology patients.

“I didn’t want to just be in a lab,” he said. “I also wanted that real-life application.”

Rogers first learned of the IU School of Medicine Scholarly Concentration Program in biomedical engineering when a former West Lafayette medical student, Andrew Thyen — now a surgery resident — was assigned to help Rogers with TBI-on-a-chip research.

“Before working in Ed's lab, I did not have a significant interest in research,” Thyen said. “That all changed after working with Ed. I believe his work will change our understanding and ability to treat brain injuries in the future.”

Now Rogers is bringing his experience as a lab leader across the street to IU School of Medicine—West Lafayette. Tews said the jam sessions with Rogers and another medical student on banjo are a bonus—they often play the “Scrubs” theme song, “Superman.”

“Having a student in their first year of medical school with his focus and impact in research is unique,” Tews said.

“Having a student in their first year of medical school with his focus and impact in research is unique,” Tews said.

IU School of Medicine and Purdue University have many collaborations, including the Engineering in Medicine partnership which fosters innovation and translation of discoveries from the lab to patients.

“Ed’s research has provided another unique way that researchers at both institutions can unite around a primary focus, which is to improve care for traumatic brain injury patients,” Tews said.

Shi is equally excited for collaborations to continue and strengthen.

“This IU medical school campus being at Purdue, a world-renowned engineering research school, is a golden opportunity,” he said.