Taryn Deenik was at her wit’s end. Her toddler, Aubree, was a virtual Houdini when it came to car seat travel. One minute, Aubree, who has autism, would be securely fastened in her car seat, and the next, she would be out of her seat hitting her siblings—often shirtless, having squeezed out of her clothes on the way through her car seat straps.

In all the distraction, Deenik was terrified of having a wreck without Aubree properly secured. Thankfully, Aubree’s developmental pediatrician, Marilyn Bull, MD, also happens to be one of the nation’s foremost experts in child passenger safety.

Bull, the Morris Green Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine, founded the Automotive Safety Program at Riley Hospital for Children in 1981. She and Green, IU School of Medicine’s second chair of pediatrics, pioneered the field of developmental pediatrics, which focuses on the treatment of children with learning and behavioral issues from infancy through young adulthood.

“By the grace of God, we were assigned to Dr. Bull for developmental care when Aubree was 6 months old, when she needed a G-tube placement because she couldn’t take a bottle correctly,” Deenik said. “Not only is she the best developmental pediatrician—she’s changed our lives. She listens. She cares. She’s nothing short of amazing.”

Bull advocated for Aubree, wrangling with Deenik’s insurance company for about six months before the company approved payment for an expensive car seat with locking mechanisms designed specifically for children with special needs.

“Dr. Bull makes a big effort,” Deenik said. “The care doesn’t stop at the door when you leave.”

Bull has been instrumental in the passage of several automobile passenger safety laws in Indiana, including the first child passenger restraint law (1984), first seat belt law (1987) and the booster seat law (2004) with her colleague Joseph O'Neil, MD, MPH.

Bull has been instrumental in the passage of several automobile passenger safety laws in Indiana, including the first child passenger restraint law (1984), first seat belt law (1987) and the booster seat law (2004) with her colleague Joseph O'Neil, MD, MPH.

In addition to helping Indiana children stay safe, Bull is a national and international presenter on several topics, including Down Syndrome and child passenger safety—especially the safe transportation of children with disabilities. Adding to her many accolades, Bull recently received the 2022 Pioneer Award from the Injury Free Coalition for Kids and gave a keynote address at the coalition’s annual conference in December.

“Dr. Bull’s research, perseverance and advocacy to implement automotive safety for children have led to a transformational culture change,” said D. Wade Clapp, MD, chair of the Department of Pediatrics at IU School of Medicine. “Her life and career display a vision to serve and better the community and nation. Dr. Bull’s passion for serving children is shown in everything that she does and inspiring to all who she works with.”

Cherry pie and car seats

Those closest to Bull say she has only “failed” at one thing—retirement. Bull, 80, joined the faculty at IU School of Medicine in 1976 and has no plans to stop seeing patients. That’s a relief for Deenik, who often tells Dr. Bull that she cannot retire until Aubree, now 9, “ages out” from seeing her pediatrician.

“People say I work too hard, but I don’t know how to do any differently because I grew up on a farm,” Bull said. “I’d come home from school as an elementary student and change my clothes and go out to the farm to pick up apples off the ground in the fall. We’d put them in crates to be taken off to Gerber's—which was 20 miles down the road—to make applesauce for babies.”

“People say I work too hard, but I don’t know how to do any differently because I grew up on a farm,” Bull said. “I’d come home from school as an elementary student and change my clothes and go out to the farm to pick up apples off the ground in the fall. We’d put them in crates to be taken off to Gerber's—which was 20 miles down the road—to make applesauce for babies.”

In the summers, her family grew cherries, selling them to tourists near the shores of Lake Michigan.

“My parents would put up a card table, and my brother and I would sit out there and sell quarts of cherries for 25 cents,” Bull recalled.

In high school, Bull was put in charge of handing out “tickets” to the migrant workers for each bucket of cherries they picked from the orchard—later to be exchanged for payment. By the time she was in college at Michigan State University, Bull wanted a different summer job.

“I told my parents the only way I was going to work at the farm was if they let me bake cherry pies to sell at the market,” she said. “The first year, I made them on our breakfast table. The second year, they fixed me a place to work in the basement, and the third year, my dad built a new office and put in a little bakery there for me to make cherry pies.”

Bull sold her first cherry pie in 1961 for 95 cents. Today, her sister, Barbara, runs the Cherry Point Farm and Market in Shelby, Michigan. Marilyn still comes “home” to work at the family farm every summer—while continuing to see patients at a Riley Children’s Health clinic in South Bend, Indiana.

To commemorate the market’s 50th year of cherry pies in 2011, the Bull sisters organized an event that combined both of Marilyn’s passions—pies and car seat safety. If they were going to host an event drawing hundreds of families, Bull wasn’t going to miss the opportunity to offer car seat installation checks by certified technicians—each trained using the national curriculum which Bull herself developed. She also auctioned off dozens of her famous cherry pies to support Safe Kids Worldwide of Western Michigan.

To commemorate the market’s 50th year of cherry pies in 2011, the Bull sisters organized an event that combined both of Marilyn’s passions—pies and car seat safety. If they were going to host an event drawing hundreds of families, Bull wasn’t going to miss the opportunity to offer car seat installation checks by certified technicians—each trained using the national curriculum which Bull herself developed. She also auctioned off dozens of her famous cherry pies to support Safe Kids Worldwide of Western Michigan.

Bull said she might have decided to stay in the family agricultural business instead of studying medicine, but “women weren’t farmers at that time.” So…they were doctors?

“That’s a good question,” Bull said with a chuckle. “My medical class at the University of Michigan was 10 percent women, and that was the talk of the faculty—how were they going to ‘handle’ 10 percent women?”

“My mother probably would’ve been happier if I was a teacher,” Bull added. “I took pre-med classes in college because I liked science, and it was sort of a challenge to myself to see if I could get accepted to medical school. My parents were happy for me when I got in.”

The male-to-female ratio of medical students was advantageous in some ways.

“When I went to internship orientation, there were three women and 30 men,” Bull said. “This guy (Scott Bruins, MD) sat next to me and talked to me all morning, and we have been now married almost 52 years.”

The word Bull doesn’t say

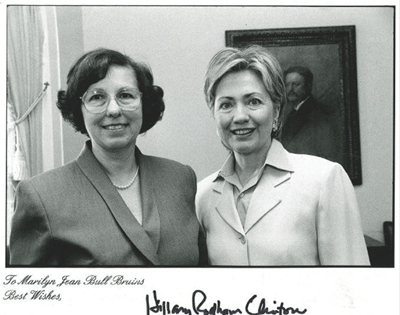

Bull has been invited to speak at national and international conferences in every U.S. state, plus 14 countries. She once shared a podium with Hillary Clinton, who was then the first lady of the United States, to speak about stroller safety during Bull’s tenure as chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Child Injury, Violence and Poison Prevention.

Bull has been invited to speak at national and international conferences in every U.S. state, plus 14 countries. She once shared a podium with Hillary Clinton, who was then the first lady of the United States, to speak about stroller safety during Bull’s tenure as chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Child Injury, Violence and Poison Prevention.

“For many years, Marilyn was one of the most experienced developmental pediatricians in the nation,” said Richard Schreiner, MD, chair of the Department of Pediatrics at IU School of Medicine from 1987 to 2009. “Her work in child safety has made worldwide impact.”

At one of her many speaking engagements, Bull was asked if there was a word not in her vocabulary. While she paused to think, her colleagues in the back of the room knew the answer immediately: “can’t.”

“I think that reflects the importance of looking for other ways to meet goals even when the means are not obvious,” Bull said. “This all has required juggling, and I hope my family and colleagues know I have done the best I can for them, our community and my world.”

In 2018, Bull was named to the Child Passenger Safety Hall of Fame by the Manufacturers Alliance for Child Passenger Safety, honoring her outstanding work in protecting children from what has historically been the most common preventable cause of death and injury in children—motor vehicle crashes.

In 2018, Bull was named to the Child Passenger Safety Hall of Fame by the Manufacturers Alliance for Child Passenger Safety, honoring her outstanding work in protecting children from what has historically been the most common preventable cause of death and injury in children—motor vehicle crashes.

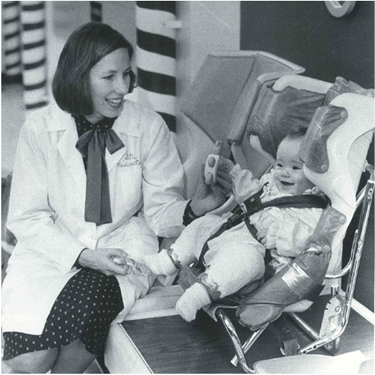

Her interest in car seats stems from her first role with Riley Children’s Health—following up with premature babies who had been discharged from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU).

“In the first three years I was here, we had one death and two permanently brain-damaged NICU graduates, not because of the wonderful care they got in the NICU or issues related to their prematurity, but because we hadn’t put them in what would have been a $25 car seat,” Bull said. “I just couldn't tolerate that.”

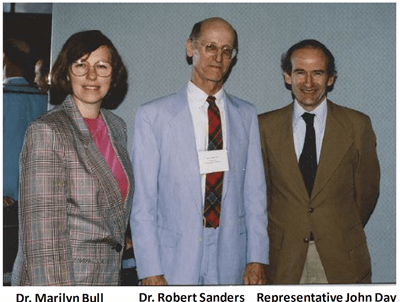

She reached out to Robert Sanders, MD, a pediatrician from Murfreesboro, Tennessee, known as “Dr. Seat Belt,” who succeeded in making his state the first to pass a child restraint law in 1977. She got a $200 grant from the Indiana chapter of the AAP to start her advocacy efforts and teamed up with Indiana Rep. John Day.

“I taught my children fine motor skills by having them put stamps on envelopes to mail out to Indiana pediatricians with information about lobbying,” said Bull.

“I taught my children fine motor skills by having them put stamps on envelopes to mail out to Indiana pediatricians with information about lobbying,” said Bull.

Even after car seats were mandated, Bull saw a problem with safely transporting low birth weight babies and other children with special needs—so she set out to create solutions. She created a preemie-sized crash test dummy, known as the “Riley dummy,” that car seat manufacturers still use in testing.

“I published the first paper that showed how to safely transport low birth weight infants in car seats,” she said.

She specialized in “protecting the forgotten children,” helping develop car beds for children in hip casts and once helping the parents of conjoined twins accomplish safe car travel prior to the twins’ successful separation surgery.

Currently, Bull is advocating for legislation to ensure the safe transport of children in ambulances and for legislation to reduce the rising numbers of children injured by guns. Since 2017, more children, adolescents and young adults have died from firearms than from motor vehicle crashes.

A champion for all children

The Automotive Safety Program Bull developed at Riley Children’s is often cited as a national resource and houses the National Center for Safe Transportation of Children with Special Needs. She and O'Neil, the program's co-medical directors, recently created the Marilyn J. Bull Automotive Safety Endowment at Riley Hospital for Children to ensure this important works continues for years to come.

The Automotive Safety Program Bull developed at Riley Children’s is often cited as a national resource and houses the National Center for Safe Transportation of Children with Special Needs. She and O'Neil, the program's co-medical directors, recently created the Marilyn J. Bull Automotive Safety Endowment at Riley Hospital for Children to ensure this important works continues for years to come.

“The program has become one of the largest developmental medicine programs in the country and is recognized across the nation for the care of children with medical disabilities,” said O’Neil, who has worked with Bull in injury prevention since his days as a resident in 1991.

“Marilyn is a very diverse professional with a lot of different interests, and she really is a founding member of developmental pediatrics, along with Morrie Green,” he said. “She goes out of her way to make sure families and children know they have someone in their corner to fight for them, to help protect them, nourish them, and grow and develop them.”

Over the years, Bull has served in leadership with numerous national organizations and has participated in several federal Blue Ribbon panels related to transportation. Her curriculum vitae includes receiving the Champion of Change Award from the White House and the U.S. Department of Transportation in 2015; the Donald F. Huelke Lifetime Member Award from the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine in 2015; and the C. Everett Koop Medal of Distinction from Safe Kids Worldwide in 2017.

Over the years, Bull has served in leadership with numerous national organizations and has participated in several federal Blue Ribbon panels related to transportation. Her curriculum vitae includes receiving the Champion of Change Award from the White House and the U.S. Department of Transportation in 2015; the Donald F. Huelke Lifetime Member Award from the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine in 2015; and the C. Everett Koop Medal of Distinction from Safe Kids Worldwide in 2017.

Although Bull has no immediate plans to retire, she knows that day will inevitably come.

“I would hope I could be remembered as a champion for all children and that, in some small way, I have made a difference and improved the lives of children and their families here, across the country and in some places around the world,” Bull said. “I feel blessed to have been able to contribute in the ways I have and only regret where I was not able to do more.”