In week one of her first faculty position at Carolinas, Hammond’s chair presented a goal for their site to become part of the TBI Model Systems program sponsored by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research, which supports multi-site research into the comprehensive care and rehabilitation of individuals with traumatic brain injury.

“All at once, everyone in the room turned and looked at me, and said, ‘And you can get us there!’ I was shocked. Why were they looking at me? I was only one week into starting my career and had no idea how to write a grant,” Hammond said.

Never one to back down from a challenge, Hammond plunged in and ultimately secured the grant; then she set to work on figuring out how to conduct the study—building the necessary research infrastructure from scratch.

Never one to back down from a challenge, Hammond plunged in and ultimately secured the grant; then she set to work on figuring out how to conduct the study—building the necessary research infrastructure from scratch.

Her involvement with TBI Model Systems has been ongoing ever since. Now, 24 years later, Hammond leads Indiana’s TBI Model System and chairs the executive committee of TBI Model Systems project directors nationwide. Hammond is the first woman in this role since the initiative was launched in 1987, leading the largest longitudinal study of TBI outcomes in the world.

“It’s a big deal,” said John Corrigan, PhD, Hammond’s predecessor in the role and director of the Ohio Brain Injury Program with The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. He’s co-authored more than 30 manuscripts with Hammond over the last two decades. “When you’re involved in any project with her, it’s almost certain she will have done the most work and been the hardest worker on the team.”

Hammond has won some of the biggest awards in brain injury research, including the Robert L. Moody Prize in 2016 given annually at the Galveston Brain Injury Conference, a think tank of about 40 experts in the field.

“To me, this award represents progress towards my career dream to change what is possible for people living with the effects of brain injury,” Hammond said.

Corrigan said Hammond “broke the glass ceiling” as a woman in brain injury research.

“The field was dominated by male leaders until Flora came along. Now she’s one of multiple female leaders,” he said. “She’s smart, she’s persistent, and she’s not intimidated. She’s a hard worker and well-trained. She was poised to be a leader. It was a matter of not letting biases at the time prevent her.”

Mentoring women leaders in brain injury research and rehabilitation

Her leadership has inspired many women in the field of physical medicine and rehabilitation. Katta-Charles credits Hammond with showing her the value of active listening.

“She wears many hats and is involved in multiple projects, but you would never know in talking to her because she is 100 percent with you in the moment and listening actively,” Katta-Charles said. “She has modeled this skill for me, and I have been the beneficiary of her excellent listening skills. I try to really listen to others, and it makes all the difference in building relationships, whether it is with your team or patients.”

“She wears many hats and is involved in multiple projects, but you would never know in talking to her because she is 100 percent with you in the moment and listening actively,” Katta-Charles said. “She has modeled this skill for me, and I have been the beneficiary of her excellent listening skills. I try to really listen to others, and it makes all the difference in building relationships, whether it is with your team or patients.”

Beyond professional excellence, Hammond has inspired “rising stars” in her field to value work-life balance.

“She encouraged me to believe that I could manage a busy and successful career and also be a wonderful wife and mother. She was clearly a role model to me, not just as a physician but as a whole person,” said Toomer. “She also showed me the importance of exercise as part of my physical and mental health.”

Hammond rises early and incorporates exercise into her daily routine, including running, Pilates and walks with her husband. Recently, she decided to take up painting as a way to further her personal growth.

“Pour painting allows me to create something without being inhibited about being precise. I keep experimenting. I’ve invited people over and helped them learn to paint; it’s been a great experience in getting out of my comfort zone,” she said. “The creative process is a constant cycle to improve the process and outcome—similar to my own self-growth, research, clinical care and leadership.”

“Pour painting allows me to create something without being inhibited about being precise. I keep experimenting. I’ve invited people over and helped them learn to paint; it’s been a great experience in getting out of my comfort zone,” she said. “The creative process is a constant cycle to improve the process and outcome—similar to my own self-growth, research, clinical care and leadership.”

Above all, Hammond’s mentees say she’s taught them by example to care for others and always do their best—the same lessons her parents taught her by their example in her formative years.

“She wasn’t one to sit down and give formal career advice. She teaches by her incredible example and mentors by encouraging the absolute best in everyone around her,” Toomer said. “She succeeded because she has a passion to take care of patients, to research to be certain that the care we are providing is the absolute best, that we have the data to prove we are doing the right thing. She always focused on the medicine and the patient, and her success is a byproduct of her focusing outside of herself.”

Women in Leadership at IU School of Medicine

Women are leading the way in helping Indiana University School of Medicine fulfill its mission to advance health in the state of Indiana and beyond by promoting innovation and excellence in education, research and patient care. The Women in Leadership series celebrates the contributions of women who have emerged as strong leaders within the medical school and in their respective fields of expertise.

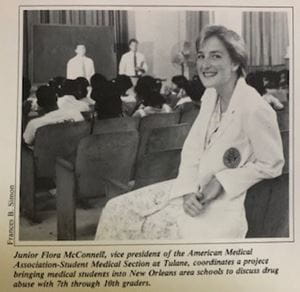

Hammond inherited an industrious nature which has guided her career in medicine. A board-certified physiatrist, she is extensively published for clinical research exploring rehabilitation and recovery after brain injury, concussion and spinal cord injury. In addition to being the Nila Covalt Professor and department chair, Hammond is chief of medical affairs for the Rehabilitation Hospital of Indiana (RHI).

Hammond inherited an industrious nature which has guided her career in medicine. A board-certified physiatrist, she is extensively published for clinical research exploring rehabilitation and recovery after brain injury, concussion and spinal cord injury. In addition to being the Nila Covalt Professor and department chair, Hammond is chief of medical affairs for the Rehabilitation Hospital of Indiana (RHI).

“It is rare to find someone in the field who has not had some contact with Dr. Hammond directly or indirectly through her teachings, patient clinics, research, peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, model systems experience, grants secured and written, etc.,” he said. “She is always willing to support anyone in our field who may need her valuable expertise on clinical, research or personal matters. She combines brilliance with compassion in ways that are both rare and needed as a clinician, researcher, educator and overall supportive colleague.”

“It is rare to find someone in the field who has not had some contact with Dr. Hammond directly or indirectly through her teachings, patient clinics, research, peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, model systems experience, grants secured and written, etc.,” he said. “She is always willing to support anyone in our field who may need her valuable expertise on clinical, research or personal matters. She combines brilliance with compassion in ways that are both rare and needed as a clinician, researcher, educator and overall supportive colleague.”

Dawn Neumann, PhD, associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at IU School of Medicine and research director at RHI, also met Hammond at Carolinas while doing postdoctoral studies, counting herself fortunate to come under her mentorship. After Hammond came to IU, she recruited Neumann, and the two have collaborated on many research studies, publications and presentations.

Dawn Neumann, PhD, associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at IU School of Medicine and research director at RHI, also met Hammond at Carolinas while doing postdoctoral studies, counting herself fortunate to come under her mentorship. After Hammond came to IU, she recruited Neumann, and the two have collaborated on many research studies, publications and presentations.

“That made a huge impact on me. My mom decided to restart her career as a dietician, and my swim coach decided to work there instead of coaching. It seemed like everyone was talking about it, at least in my world,” Hammond recalled. “I visited my mom and volunteered there. I knew immediately I wanted to be a physician who worked in a rehabilitation hospital.”

“That made a huge impact on me. My mom decided to restart her career as a dietician, and my swim coach decided to work there instead of coaching. It seemed like everyone was talking about it, at least in my world,” Hammond recalled. “I visited my mom and volunteered there. I knew immediately I wanted to be a physician who worked in a rehabilitation hospital.”

This early experience fueled a passion which has extended throughout her career to fight the prevailing misconception that recovery ceases at the one-year mark post-TBI. For the last decade, Hammond has led an initiative to recognize TBI as a chronic condition with gains in recovery possible many years post-injury.

This early experience fueled a passion which has extended throughout her career to fight the prevailing misconception that recovery ceases at the one-year mark post-TBI. For the last decade, Hammond has led an initiative to recognize TBI as a chronic condition with gains in recovery possible many years post-injury.