“My parents’ emphasis to our family was that we were privileged to have what we had, and we needed to use that privilege to help those who were less fortunate,” said John. “That stuck with me, and when I decided to choose careers, I couldn’t find one that seemed better suited to serving the underserved than medicine.”

While enrolled at the University of Michigan Medical School, John was first exposed to clinicians who simultaneously treated patients and completed research in their areas of expertise. His decision to embark on a physician scientist path was solidified during this period after spending time in Bangladesh and Nigeria working with children afflicted by malaria.

While doing an international health fellowship in Nigeria during his residency, John saw the devastating effects of malaria on the children of Nigeria. Yet he did not know of any pediatricians funded by the National Institutes of Health to conduct clinical or translational research in malaria. His immersive experiences in Africa, coupled with guidance from several esteemed mentors, set him on the trajectory to becoming a globally recognized expert in pediatric infectious diseases.

“There was this huge problem—one of the top five killers of children in the world—and I thought, ‘Why aren't people who take care of children involved in the research when we know child health best?’” John recalled. “That’s what drew me to go to pediatric infectious disease and to focus my research on malaria.”

Pivotal moments with passion

With over 30 years of research experience and collaboration to his credit, John remembers numerous career highlights, with a few being particularly pivotal.

Soon after deciding to pursue malaria-based research following his pediatrics residency, John joined the pediatric infectious diseases program at Case Western Reserve University. Working alongside one of his influential mentors James Kazura, MD, they researched areas most susceptible to malaria epidemics.

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites transmitted through the bites of infected mosquitoes. While it is well-known malaria is common in tropical countries, John and Kazura wanted to learn more about immunity’s role in areas with malaria epidemics. This led to John’s first studies in Kenya focusing on whether cellular and antibody responses to malaria decreased as transmission rates dropped. His findings confirmed they did, supporting the hypothesis that loss of immunity could contribute to malaria epidemics.

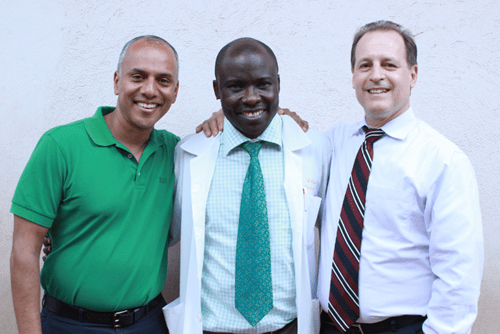

John said the studies in Kenya have been ongoing for more than 25 years, made possible with support from valued collaborators and trainees-turned-peers, like George Ayodo, PhD, MSc, BSc.

“The work started with Dr. John, but we’ve been able to expand the research and have more collaborators on board,” Ayodo said. “The research is still growing, and he has continued to be very supportive of us. Many of his students now hold key positions in their community and in Kenya.”

Another significant area of John's career is centered around severe malaria research. He and his colleagues, including Paul Bangirana, MSc, PhD, discovered that children with cerebral malaria and severe malarial anemia develop neurodevelopmental impairment that can last for two or more years after the initial episode. These findings emphasized malaria's impact extends beyond immediate illness and death, affecting long-term brain function and future life prospects.

“Our group is one of very few that’s studying the effects of malaria on the brain,” said Bangirana, a clinical psychologist and associate professor at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda. “Our studies have consistently resulted in progressive funding, including obtaining training grants in Uganda that have helped to train other Ugandans in neuropsychology, immunology and epidemiology in pediatrics.”

Bangirana and John have been collaborating since 2003, combining their expertise in pediatrics and psychology to secure numerous awards from the National Institutes of Health. Their funding has supported the training of more specialists and expanded their impact beyond Kampala, building capacity in other regions.

“Through the research we are doing, we also provide free treatment,” Bangirana said. “Participants benefit from the quality care that comes as a result of being part of a stringent research study with clear protocols.”

“Through the research we are doing, we also provide free treatment,” Bangirana said. “Participants benefit from the quality care that comes as a result of being part of a stringent research study with clear protocols.”These studies also led to further research identifying a high mortality rate among children within a year after hospital discharge, prompting investigations into the causes of these deaths. Their involvement in a larger study on malaria chemoprevention for children with severe anemia showed significant success in reducing hospital readmission and death rates. This led the World Health Organization to recommend post-discharge malaria chemoprevention in high transmission areas, marking a significant advancement in malaria care.

“The costs of malaria are not just when a child has the disease, they also occur throughout the child’s life and into adulthood. It may affect their brain and therefore their ability to get work and provide for their family,” John expressed. “Now we’re thinking about interventions that will prevent, or at least significantly decrease, damage from occurring in the first place.”

In addition to his groundbreaking work on severe malaria, John has also made significant contributions to sickle cell disease research due to the blood disorder’s genetic link to malaria protection. If a person has a single copy of the sickle cell gene (sickle cell trait), they are highly protected against developing severe malaria. However, having two copies of the gene results in sickle cell disease, which can lead to more severe or fatal complications.

“I was working in areas where there was a lot of malaria and where there's a lot of malaria then there's a lot of sickle cell disease,” he said. “In some areas that we study, 25% of the kids have sickle cell trait so it's incredibly common because it protects against severe malaria but that also means that as many as 4% of children will have sickle cell disease, which can be deadly.”

To address this issue, John partnered with pediatric hematologist Russel Ware, MD, PhD, from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and pediatrician Robert Opoka, MD, PhD, from Mulago Hospital in Uganda, to study the safety and efficacy of hydroxyurea for children with sickle cell disease. While hydroxyurea was commonly used in the United States for this purpose, it had only been recognized as a cancer treatment in African countries. Their study, known as NOHARM MTD (Novel use Of Hydroxyurea in an African Region with Malaria – Maximum Tolerated Dose), showed that hydroxyurea was not only safe but also reduced pain crises, transfusions and hospitalizations. It also decreased infection risks, including malaria.

“The NOHARM study actually changed Uganda guidelines,” John acknowledged. “They now recommend hydroxyurea for kids and adults with sickle cell disease and there's work towards making hydroxyurea more affordable so every child can be on it.”

John's collaboration with Opoka, who is currently the associate dean of undergraduate medical education at Aga Khan University, is one of his most significant partnerships. Over the past twenty years, they have conducted numerous groundbreaking studies on malaria and sickle cell disease, including the NOHARM MTD study. Their efforts also led to the creation of Global Health Uganda (GHU), a grant management institute that equips researchers, particularly in Uganda, with the infrastructure needed to effectively manage research funding.

"Our work together has helped train several young Ugandan scientists, including 10 who have completed their PhDs to date. We have produced over 200 articles in peer-reviewed journals, contributing to policy guidelines at the World Health Organization and at the national level," Opoka said. “The work continues, especially through GHU’s employment of 200 Ugandans. What Dr. John has accomplished here and continues to do is truly remarkable and outstanding.”

Building a career through mentorship and collaboration

As he reflects on the numerous milestones of his career, John is diligent in thanking and recognizing the collaborators and relationships that have supported him throughout his career and influenced his approach to both science and patient care.

While he didn’t conduct research directly with Carol Kauffman, MD, Francis Collins, MD, PhD, or Janet Gisdorf, MS, DSC, during his time at the University of Michigan, John said their curious minds and clinical expertise taught him to think broadly about patient problems and research opportunities. Similarly, his early connections at Case Western Reserve with Kazura and Christopher King, MD, PhD, further emphasized the value of scientific curiosity and excellent interpersonal skills. John credits all his mentors for demonstrating the importance of treating everyone around them with respect and empathy, regardless of their role or title.

“They all treated everybody with respect and genuine empathy, and that always stuck with me,” he said. “I wanted to be a good scientist and a good doctor, but more importantly, a good person that people respect for their work and how they treat others.”

Opoka, who has worked with John since 2004, can attest to how deeply John cares about the communities and colleagues he serves.

“He cares not only for the patients, but he also cares for his colleagues and the science,” Opoka expressed. “You can see it in his eyes, hear it in his voice and feel it in your spirit. I, and many of us who have worked with him here in Uganda, owe him a lot.”

“He cares not only for the patients, but he also cares for his colleagues and the science,” Opoka expressed. “You can see it in his eyes, hear it in his voice and feel it in your spirit. I, and many of us who have worked with him here in Uganda, owe him a lot.”Ruth Namazzi, MBChB, MMEd, from Makerere University, is another one of John’s longstanding collaborators who can speak to his character and dedication. Together, they have conducted several pivotal studies that have expanded the understanding of sickle cell disease and malaria. Recently, they co-authored a groundbreaking study revealing that Ugandan children exhibit partial resistance to the primary treatment for severe malaria in African children. Namazzi admires John for his enduring commitment to Uganda, emphasizing the research legacy they’ve built there.

“The capacity we’ve built, both in the clinical and research fields, is huge. I think there’s a part of him that is African,” she said with a smile. “He just loves children and is driven to make a difference. He visits Uganda almost four times a year, which is a lot. He comes not only to ensure everything is going well but also to check on us. He respects everyone he works with.”

John has consistently maintained this compassionate approach over the years, whether collaborating with teams in Uganda and Kenya or working with colleagues locally. In Indiana, John leads a dedicated research team at the Ryan White Center for Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Global Health and the Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research comprised of Dibya Datta, PhD; Andrea Conroy, PhD; Giselle Lima-Cooper, PhD; Nathan Schmidt, PhD and Tuan Tran, MD, PhD.

John credits his determined team and the supportive environment at IU, where he’s worked since 2015, for playing a key role in his career progression. Advancing knowledge in global health and infectious diseases requires a specialized infrastructure, which makes his frequent trips to clinical research sites in Africa essential. These visits ensure the proper maintenance of equipment, supplies and personnel support—all of which demand significant financial resources and trust. John said he’s fortunate to receive this support from IU, Riley Children’s Health and especially from generous donors at Riley Children’s Foundation and IU Dance Marathon (IUDM).

The first IU Dance Marathon was held in 1991 in honor of Ryan White, a young Hoosier and Riley Hospital patient who gained international recognition for his AIDS advocacy before passing away from the disease in 1990. Since then, the annual event has raised over $50 million, helping to endow the research center named in White’s honor and expanding its support to other pediatric research efforts at the Wells Center.

“IUDM created the endowment that supports so much of the mission of our division, and without that endowment, we wouldn't exist in the same way,” John said. “I don't know of any other institution that gives the kind of support we receive. I have loved working here. It's really an exceptional place.”

John’s mentors and collaborators have influenced not only his work but also how he trains aspiring scientists. He encourages them to embrace his guiding principles: be curious, be honest, be precise, be kind and be persistent.

He believes curiosity drives bigger goals and unexpected discoveries, while honesty is essential to the scientific process. John deems precision as an underemphasized but critical aspect of great science, and he tells his students that attention to detail is the single most important skill to develop and practice as a scientist.

As a longtime collaborator and mentee, Bangirana has witnessed John's principles in action. He described John as patient yet firm in his high standards.

“He makes you want to aim a bit higher than you think you can aim because he has a very high bar for quality,” Bangirana said. “He inspires growth, and I think that’s good because it trickles down and develops the same kind of behavior and mentality in others.”

Similarly, Namazzi, who has nearly 15 years of experience learning from and working with John, attests that he always has his mentees’ best interests at heart.

“He looks out for his mentees, and everything he does is geared toward their success,” she explained. “Everyone says, ‘I wish you well,’ but Chandy actually means it.”

John also stresses that kindness fosters meaningful connections and that being considerate of others' needs is especially important when working to uplift disenfranchised and marginalized populations. And finally, persistence is key, as the pursuit of science often involves facing rejection.

“The goal in science isn’t about titles, publications or awards. It’s about uncovering the truth behind the process you’re studying and sharing what you’ve learned,” he said.

Inspired by the arts and driven by service

Another skill John values as a scientist is writing, a passion he’s held even longer than his love for medicine. In addition to his scientific achievements, he has published poetry, essays and short stories. He’s found a way to blend his two passions by writing pieces that reflect his unique experiences working in global health.

Another skill John values as a scientist is writing, a passion he’s held even longer than his love for medicine. In addition to his scientific achievements, he has published poetry, essays and short stories. He’s found a way to blend his two passions by writing pieces that reflect his unique experiences working in global health.“I'm a scientist at the core, but I'm such a lover and believer of and supporter of the arts because that's one of the things we live for as humans,” he divulged.

John’s appreciation for the arts extends to his personal support system as well. He speaks fondly of his partner, Andy, a gifted pianist whose selflessness, music, humor and encouragement have been a constant source of joy and inspiration in his life and work.

“He makes my world a better place, and I want to pass on that gift to others by trying to make their world better too,” John said.

Through all his responsibilities and endeavors, John remains deeply committed to serving the underserved and staying grounded in gratitude. His parents instilled this mentality in his family from an early age, shaping not only his own path but also the careers of his brother and sister, who are also both doctors working in global health.

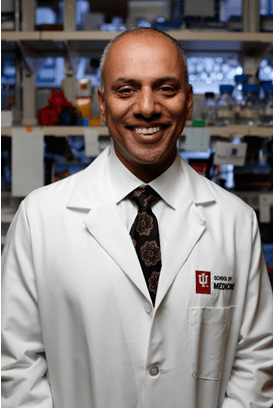

In early 2024, John was appointed as a Distinguished Professor at Indiana University, the highest academic rank a faculty member can achieve. This title recognizes extraordinary scholarly achievement and leadership in one's field, and for John, it represents a culmination of years of impactful research, mentorship and collaboration. Looking ahead, he has more ambitious research plans including new clinical studies in Uganda focused on severe malaria risks and interventions. But for John, the ultimate measure of career success is celebrating the impact made with support from those around him.

“My work is nothing if not collaborative,” he said. “I very much view the distinguished professor appointment as reflective of our collective work and not for anything I did on my own.”