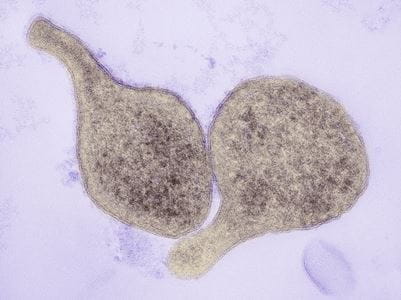

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) can cause genital symptoms, like vaginal itching or spotting, burning with urination, and vaginal or urethral discharge. When patients are diagnosed with an STI, they are treated with CDC-recommended first-line antibiotics. They are also instructed to abstain from sex until they have finished their antibiotics and their symptoms have resolved because it is thought that resolved symptoms indicates that the infection has been cured. But researchers from Indiana University School of Medicine suspected that one emerging STI, caused by a tear-drop shaped antibiotic-resistant bacterium called Mycoplasma genitalium (“MG” for short), may not behave like other STIs. Their concern is that treatment of antibiotic-resistant MG might be enough to kill most, but not all, of the MG bacteria, resulting in patients feeling better and resuming sexual activity while still having an ongoing MG infection.

To test this hypothesis, IU School of Medicine researchers Evelyn Toh, PhD, Stephen Jordan, MD, PhD, and their IU School of Medicine research team conducted a NIH-funded study of 280 men who had presented to the Marion County public health clinic with STI symptoms. The investigators collected urine from them for STI testing, treated them with the CDC-recommended antibiotic azithromycin, and then asked them to return one month later for a “test of cure” visit to assess if they had cleared their STI. When study participants returned, they were asked if they took other antibiotics, if their partner was treated or if they had a new partner, and if they engaged in unprotected sex since they received treatment. They were also retested for six different STIs. After excluding participants that could have been reinfected or that took other interim antibiotics, one hundred and twenty-one men were included in the final study group: fifty-two had chlamydia, seven had Ureaplasma urealyticum, sixteen had MG, and the rest either had a mixed or unknown infection. At the “test of cure” visit, men were considered cured if they had cleared their STI (e.g., all STI testing results were negative). They were also asked if their signs and symptoms of urethritis had resolved.

The investigators found that cure rates were very high in men with chlamydia, Ureaplasma urealyticum, or the mixed/unknown group and feeling better correlated strongly with the infection being cleared, but not in MG infections. In men with MG infections, most men felt better after treatment, while only about a third (31%) were cured with antibiotics. In fact, most men with MG infection had a “disconnect of cure types” after treatment, where they had a clinical cure (they felt better, and their symptoms resolved) without a microbiological cure (antibiotics failed to clear their infection).

The findings show a “cure disconnect” in MG infections which should be a warning to both clinicians and patients. “When treating MG, feeling better does not always mean the infection was cured with antibiotics,” said Toh. Although following their providers instructions to wait until symptoms have resolved before resuming sex is correct for other STIs, patients with MG infection may be unknowingly spreading it to their partner if it isn’t cleared by antibiotics. The IU School of Medicine study results also disagree with one part of the CDC’s recently released 2021 STI Treatment guidelines. “All STI guidelines from other countries recommend routine MG testing when symptoms are present and a test-of-cure assessment after treatment,” said Jordan. But, the CDC’s updated guidelines do not have the same recommendation. Jordan adds, “our study findings indicate that the CDC should reevaluate its recommendation as routine testing for MG and a test of cure assessment is an important first step in slowing the spread of MG infections.”

IU School of Medicine researchers find that feeling better after treatment for sexually transmitted infections does not always mean cure, especially with Mycoplasma genitalium

IU School of Medicine Nov 23, 2021

Author

IU School of Medicine

With more than 60 academic departments and specialty divisions across nine campuses and strong clinical partnerships with Indiana’s most advanced hospitals and physician networks, Indiana University School of Medicine is continuously advancing its mission to prepare healers and transform health in Indiana and throughout the world.

The views expressed in this content represent the perspective and opinions of the author and may or may not represent the position of Indiana University School of Medicine.