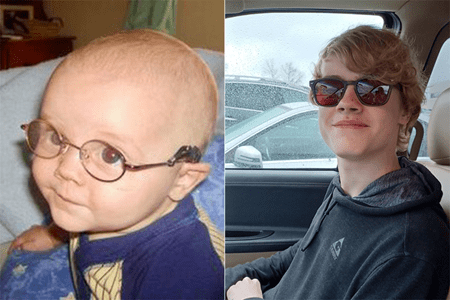

By the time her son was 2 months old, Stephanie Mowery knew something was wrong with his vision.

“He couldn’t focus on anything, and his eyes shook really bad all the time,” she said.

Throughout his life, Evan, now 16, has not been able to see in color. He also has low vision and severe sensitivity to bright light. A never-ending series of special glasses and lens filters could never fully address his issues. And there was always the lingering, often-unspoken worry at the pit of Mowery’s stomach—would her son one day go blind?

“We tried to teach him Braille, which he hated,” she said. “And we bought our house based on it having a whole upstairs with a separate entrance Evan could use as an adult if he could not live independently.”

Thankfully, Evan now has a definitive diagnosis—achromatopsia—and a giant relief for the future with a stable prognosis. The big moment came about nine months ago during a call with Erin Conboy, MD, co-director of the Undiagnosed Rare Disease Clinic (URDC) at Indiana University School of Medicine.

Thankfully, Evan now has a definitive diagnosis—achromatopsia—and a giant relief for the future with a stable prognosis. The big moment came about nine months ago during a call with Erin Conboy, MD, co-director of the Undiagnosed Rare Disease Clinic (URDC) at Indiana University School of Medicine.

“It was very exciting and a huge relief,” said Mowery, who still tears up when she talks about receiving Evan’s long-awaited diagnosis. “It was emotional because it was confirmation that my baby won’t go blind.”

After 15 years of uncertainty, Evan’s diagnosis in April 2022 means he is now eligible for funding programs to cover the cost of related expenses, and he may be eligible for a clinical trial for achromatopsia in the future—potentially reversing some of the disease’s effects on his vision through gene therapy.

Genetic disease: The Medical Frontier

The human body has about 25,000 genes. Scientists only know what 5,000 of them do. Most patients who come to the URDC have already had the best genetic testing available and still don’t have answers because their condition stems from one of the 20,000 unknown genes.

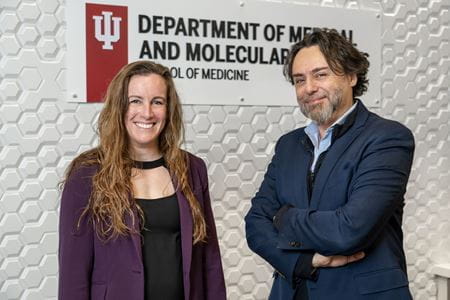

“Rare disease is like a frontier,” said Francesco Vetrini, PhD, who co-directs the rare disease clinic with Conboy. “We are looking at a mystery, so we use all the arsenal available—the most advanced technologies.”

Vetrini and Conboy, both assistant professors of clinical medical and molecular genetics at IU School of Medicine, bring complimentary backgrounds to approach these medical mysteries. As a clinical geneticist, Conboy works directly with the patient while Vetrini does behind-the-scenes sleuthing through advanced computer analysis using artificial intelligence to identify gene anomalies.

Vetrini and Conboy, both assistant professors of clinical medical and molecular genetics at IU School of Medicine, bring complimentary backgrounds to approach these medical mysteries. As a clinical geneticist, Conboy works directly with the patient while Vetrini does behind-the-scenes sleuthing through advanced computer analysis using artificial intelligence to identify gene anomalies.

“We are like yin and yang,” Vetrini said. “She looks from the outside in, and I look from the inside out. In the end, we get the right diagnosis.”

Each case involves collaboration with a global network of researchers through gene matching databases to help the URDC find similar cases with the same affected gene. The URDC also works with the Indiana Biobank for genomic sequencing of bio-samples. The patient’s parents are often tested, as well, to uncover recessive gene mutations that may have been inherited.

“We’re all carriers for between one and five disorders, on average,” noted Conboy.

The novel methods the URDC uses result in deep phenotyping of each patient. When a case is potentially solved, it’s presented to the Genome Board at IU School of Medicine, which includes biomedical geneticists, genetic counselors, disease and genome experts, lab directors, analysts, rare disease postdocs and other interested physicians or researchers.

The URDC welcomes collaboration from IU colleagues who have interest and expertise in genomics and is currently seeking a postdoctoral fellow to join their team of rare disease super-sleuths.

“For someone who wants to put their PhD scientific knowledge into a field where you have a tangible impact on patients and families, this is rewarding work,” said Vetrini, who earned his PhD in medical genetics in Naples, Italy, and came to IU School of Medicine in 2018 as an ABMGG fellow in the Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, focusing on clinical genomics and novel disease gene discovery.

Since opening in 2020, the URDC has solved about 20 percent of the genetic mysteries which have been referred to the clinic. That number is more impressive than it might seem considering these are the “cold cases” of genetic disease, often requiring new gene discovery before they can be solved.

Since opening in 2020, the URDC has solved about 20 percent of the genetic mysteries which have been referred to the clinic. That number is more impressive than it might seem considering these are the “cold cases” of genetic disease, often requiring new gene discovery before they can be solved.

In 2021, the URDC—in partnership with IU Health—was officially designated as a Rare Disease Center of Excellence by the National Organization for Rare Diseases (NORD). The discoveries made at the URDC increase the global medical community’s understanding of human genetic variants and rare diseases.

Because rare diseases, by definition, affect a small percentage of the population, funding is a challenge. Research grants typically go toward diseases affecting many people. The URDC welcomes donations of any size so the clinic can continue its work to find diagnoses for patients with mystery diseases.

Since 2020, 84 patients and 148 of their relatives have been enrolled in the clinic. Demand for the URDC’s services is increasing. Last year, the URDC received 88 referrals from physicians on behalf of their patients.

All of the clinic’s genetic sleuthing services are free to patients—a big relief for families that have already spent thousands in an attempt to manage an unknown disease.

“I scream how thankful we are for them,” Mowery said. “We would be very lost without them. We will always be grateful for Dr. Conboy and everything her team has done for us.”

“I scream how thankful we are for them,” Mowery said. “We would be very lost without them. We will always be grateful for Dr. Conboy and everything her team has done for us.”

Sometimes, as in Evan’s case, there are aids or therapies made accessible by a diagnosis. Other times, a disease is so rare that effective therapies do not yet exist. Even then, a diagnosis can bring closure and a more accurate prognosis of disease.

“A diagnosis is big deal for peace of mind,” Conboy said. “Once you know what you’re dealing with, your mind can stop all those anxious thoughts and move forward.”

Success in Ocular Genetics

Pediatric ophthalmologist Kathryn Haider, MD, first saw Evan Mowery when he was 5 years old. Although she suspected he had an inherited condition, Haider had no way to delve deeper. It would be years before genetic testing would become available.

What she could determine was that his cones—a type of photoreceptor in the retina needed for color vision—were not functioning. He had low vision and was extremely sensitive to light. He nearly got kicked out of daycare, his mother said, because he hit other children if he was startled by a fast approach from the side—he couldn’t see them coming. It was also difficult for Evan to participate in sports.

What she could determine was that his cones—a type of photoreceptor in the retina needed for color vision—were not functioning. He had low vision and was extremely sensitive to light. He nearly got kicked out of daycare, his mother said, because he hit other children if he was startled by a fast approach from the side—he couldn’t see them coming. It was also difficult for Evan to participate in sports.

In 2019, Haider started an ocular genetics clinic at Riley Hospital for Children at IU Health with Conboy and genetic counselor Katie Anderson, MS.

“The idea was to have a collaborative place to start to understand inherited eye disorders more clearly and to get a genetic diagnosis in addition to a clinical diagnosis,” Haider explained.

Prior to the clinic’s opening, pediatric ophthalmologists at Riley were able to diagnose a genetic eye disease in just 4 percent of suspected cases. Since the clinic’s opening, they have successfully diagnosed 55 percent of those cases.

For most of these patients, genomic testing brought the answers. For Evan, diagnosis was more complicated. His clinical presentation strongly pointed to achromatopsia; however, as a recessive condition, there needed to be a pair of affected genes (alleles). It was baffling when whole exome testing showed just one “misspelled” allele.

For most of these patients, genomic testing brought the answers. For Evan, diagnosis was more complicated. His clinical presentation strongly pointed to achromatopsia; however, as a recessive condition, there needed to be a pair of affected genes (alleles). It was baffling when whole exome testing showed just one “misspelled” allele.

Evan needed the deep sleuthing only the URDC could provide. As Vetrini delved into whole genome sequencing, he discovered the other misspelling lurking in what scientists call “junk DNA”—DNA that does not code for genes.

The URDC team found the “smoking gun” to finally solve Evan’s case.

His diagnosis means he is now eligible for the state-run Vocational Rehabilitation Program which helps people living with disabilities to achieve their employment goals. This program will pay for ocular equipment like specially filtered glasses, sunglasses and contact lenses. Evan also will qualify for bioptic driving, a telescopic system used while driving that improves the sharpness of far vision.

His diagnosis means he is now eligible for the state-run Vocational Rehabilitation Program which helps people living with disabilities to achieve their employment goals. This program will pay for ocular equipment like specially filtered glasses, sunglasses and contact lenses. Evan also will qualify for bioptic driving, a telescopic system used while driving that improves the sharpness of far vision.

That’s big news for a 16-year-old who thought he would never be able to drive.

“The URDC completely changed our lives,” Mowery said. “We never dreamed we would have answers. Now we know Evan will be able to live independently. As a parent, the weight that takes off is huge. It’s such a relief.”