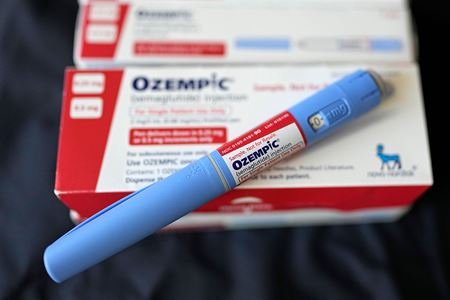

Ozempic is suddenly a household brand name, akin to Aleve, Advil, or Nyquil. Many people are calling Ozempic, and other drugs like it, “miracle drugs.” Ozempic and Mounjaro are part of a class of drugs called GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1s for short). Ozempic was approved by the F.D.A. in 2017, while Mounjaro, Ozempic’s primary competitor, was approved in 2022. Both were approved in the U.S. by the F.D.A. to help lower blood sugar. Soon after the drugs came onto the market, they were found to be quite useful to lose weight, which led the companies to develop analogous forms of the diabetes drugs that were designed and approved for weight loss.

Ozempic’s active ingredient, semaglutide, was approved by the F.D.A. for weight loss in the form of Wegovy in 2021; and Mounjaro’s active ingredient, tirzepatide, was approved for weight loss in the form of Zepbound in 2023. Being a treatment for obesity isn’t the only discovery about these drugs that have been made since they’ve come onto the market. Scientists are finding that the drugs may be useful to treat addiction, dementia, and heart disease (CNBC). Wegovy, in May 2024, was approved by the F.D.A. for the treatment of heart disease in people with obesity (FDA). With heart disease being the leading cause of death in the U.S., and obesity as the leading cause of heart disease, these drugs bring a lot of promise to two of America’s most-pressing health problems.

The increase in use of these drugs, though, can seem alarming. Data analyzed by Epic Research showed an increase in use of these drugs by 40-fold between 2017 and 2021, estimating that 6 million Americans are now on either Ozempic or Mounjaro. CNBC, analyzing data for GLP-1 drugs (Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, Zepbound) found that 9 million prescriptions of them were written in Q4 of 2022. This means that roughly 2 - 3% of the population in the United States may now be taking one of these drugs. CNBC also reports that a study found that, now that Wegovy is approved to treat heart disease in obese patients, more than 3 million Americans on Medicare could be eligible for prescription coverage of these drugs, noting that the program’s budget could be strained as Wegovy is now covered by their Part D prescription plan.

The increase in use of GLP-1s is alarming for two reasons: (1) The first reason that the increase in use of GLP-1 drugs is concerning is their little-known long-term side effects and potentially unknown short-term side effects. The drugs’ benefits are clear, but their vast benefits could also be a double-edged sword. Due to the increase in use, science may need time to “catch up” on the side effects – as in, to determine both short-term and long-term side effects as the drugs are used for different conditions and for longer periods of time. For example, one of the first GLP-1 drugs that entered the U.S. was Victoza. Victoza was approved in 2010, but in 2013, the FDA issued a warning to consumers of “possible increased risk of pancreatitis and pre-cancerous findings of the pancreas.” But we don’t have to look at previous generations of GLP-1s so see the risk that unknown side effects have. In January 2024, the FDA announced it was evaluation reports of hair loss and suicidal thoughts in patients taking Ozempic, Mounjaro, or Wegovy. So, we have seen successful GLP-1 drugs receive warnings years after being on the market for previously unknown side effects, in both an older and newer GLP-1 drugs. We must keep these cases in mind as these drugs are adopted widely as treatments for various diseases.

(2) The second reason that the increase of use is alarming is because of effects on patients’ access to their prescribed drugs. As mentioned previously, the price and wide-spread eligibility for these drugs is causing Medicare’s Part D budget to become strained. The current price, which is partially a function of supply / demand, is putting pressure even on institutions’ abilities to keep the drugs stocked. On an individual level too, the imbalance of supply and demand of these drugs has caused concerns. CBS reports that some diabetics are having a hard time having consistent access to these drugs. The limited supplies currently experienced by patients with diabetes are not purely a function of supply and demand, but also who doctors are prescribing the drugs to.

Data analyzed by Trillian Health, and reported by CNN, shows that a third of patients on Ozempic have no history of diabetes. This means that doctors are prescribing the drug “off-label,” presumably for another condition, such as weight loss. The off-label prescription of Ozempic is up to a third, or 33%, from 16% in 2021. Many doctors may feel as though they have no choice but to prescribe Ozempic to their patients who are clamoring for semaglutide to help in their weight loss. Even if doctors wanted to write a prescription for Wegovy, they may not have been able to. Novo Nordisk, the company behind Ozempic and Wegovy, says that they are years away from catching up to the demand of their drugs, and that they have stopped producing starter doses of Wegovy altogether, as they are struggling to keep up with the current number of patients on the drug.

And patients of varying races are having different experiences in getting prescribed these drugs. According to CNN, “more than 70% of semaglutide prescriptions have gone to White patients… White people are about four times more likely than Black people to have a prescription for a semaglutide medication, despite having nearly a 40% lower prevalence of diabetes and a 17% lower prevalence of obesity.” So, White patients are receiving the vast majority of semaglutide prescriptions (Ozempic and Wegovy) by percentage, despite having a lower prevalence of both diabetes and obesity. But this has been steady since 2018. Therefore, this issue may not be related to supply and demand; but rather, the fact that not a single public insurance has covered these drugs yet. This changed significantly with the approval of Wegovy for heart disease in patients with obesity, as this allows Medicare to make patients eligible for the drug. Although Medicare can now make more than 3 million patients eligible for Wegovy, this doesn’t address the gap in coverage of Ozempic and Mounjaro for diabetic patients between private and public insurance. This gap has presumably resulted in the four times difference in prescription rates between White and Black patients.

GLP-1s are seemingly miracle drugs. They are already approved for type-2 diabetes, weight loss, and heart disease. Scientists are studying them as potential treatments for addiction and dementia. This has led to a steep increase in use and prescription of these drugs, resulting in 2-3% of Americans reportedly being on them. There are two significant issues that this increase of use has caused: (1) the risk of unknown side-effects and (2) patients’ access. Victoza, a GLP-1 drug released in 2010, had side effects discovered about it, eventually resulting in official warning from the FDA in 2013. Additionally, the FDA was “evaluating reports” of hair loss and suicidal thoughts in patients taking Ozempic, Mounjaro, or Wegovy. These types of events will continue as the drugs are on the market for longer (as long-term side effects may become known), and as the drugs are used for different conditions (as other side effects may be found). Doctors must be conscious of these facts, and patients should be educated.

The second cause for concern stemming from an increased use is patients’ access. Some diabetics are reportedly having trouble accessing their previously prescribed drugs. This is ultimately from the supply and demand discrepancy but has also been triggered by doctors prescribing Ozempic off-label at higher rates, leading to Ozempic being used for weight loss and other conditions. There is also a huge barrier for Black patients trying to access these drugs, especially as none of these drugs was covered by a public health insurance in America until recently. And as of now, Medicare may make eligible about 3 million patients which have both heart disease and obesity for Wegovy. Although this is a big step, it doesn’t address the racial gap between diabetics who are eligible for these drugs. Diabetics on public insurance currently have no access to these drugs, and under current guidance, it’s unclear when that would change.

Pierce Logan is a Graduate Assistant at the Indiana University Center for Bioethics.